Introduction

An entry level chess player looks at an 8×8 chessboard.

He considers which piece to move next. Diligently, he even tries to think one or two moves ahead. At the beginning of a game that works easily. Everything is still in order and there are not so many different moves to do. But after half an hour there is a complex battlefield in front of him that he is not capable to grasp completely anymore. The number of moves is too big, and he lacks the tactical knowledge to see one or two moves into the future anymore.

If a grandmaster confronts the game on which the beginner is battling for half an hour, he does not see single pieces, he sees a pattern, he sees who is stronger, who is weaker, who has the advantage and which pieces are playing a relevant role. He sees all kind of strategies.

Take a volleyball player and show him pictures of a game in which the ball was touched away. The beginner would have to guess the position of the ball. The experienced player would correctly pinpoint the exact position of the ball.

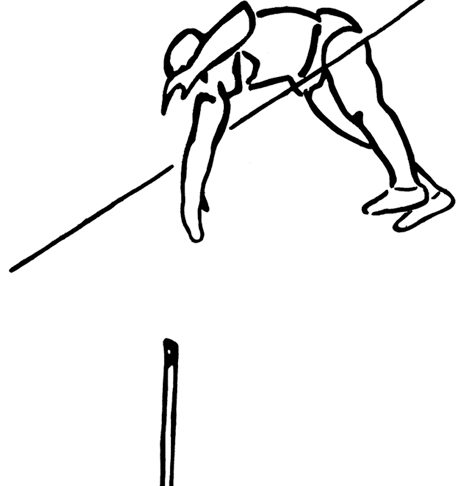

One last example. A tennis player is shown a video of the serve of an opponent player and the video is stopped at the exact moment in which the ball touches the racket. Where is the opponent going to place the ball? The beginner has no clue. But the professional can predict the direction. If you would edit and cut the arm and the grip out of the video, then he would also be clueless about what corner the serve would reach.

Automatism = Chunks

These automatisms of experienced sportsmen and chess players are called “chunks.” The brain thinks “in a larger whole”, in schemes, in abstraction. Chunks are the outcome of (very) big learning processes.

If Chunks are created after 100 hours, 1000 hours or 10.000 hours, depends on how efficient the individual learns, it also differs from person to person and on the activity in question.

In this context, reference is usually made to the „10,000 hours“ rule attributed to K. Anders Ericcsonn from Florida State University (see my book recommendation “Peak”). This number was strikingly disseminated by the book author Malcom Gladwell in his book „Überflieger“.

After this introduction to the topic, now we go specifically into pole vault.

There are more complex occupations and simpler ones. Expertise in chess- or playing the violin are one of those activities in which 10.000 hours of practice appear be a good approximation (or, according to Prof. Ericcson, roughly double). The 10km run can presumably not be classified in this category as far as cognition is concerned. This should not amount to condescension, the 10km run simply brings different challengers on the table, to those a chess grandmaster or a violin virtuoso are confronted.

I do not see myself able to present here on to where exactly the pole vault is classified into. At least, among the track and field disciplines, it would seem to be at the forefront of the most demanding ones.

The pole vault brings many variables into play:

-Height

-Size / weight ration

-Ratio of the length of the extremities (arms and legs) in comparison to the trunk

-Genetic predisposition of the muscles, especially the leg, highlighting the calf muscles

-Run-up speed

-Takeoff force

-Pole length

-Pole hardness

-Grip in relation to pole length

-Technique:

-Running posture

-Presentation/Lowering of the pole?

-Takeoff point

-Takeoff angle

-Takeoff position

-Swing Up

-Inversion and turn?

-etc.

We leave the beginner out here, he is easily overwhelmed anyway, regardless of whether he is a beginner athlete or a coach.

The advanced athlete or coach knows what it is all about (run, takeoff, swing up, inversion and turning), but he still thinks in terms of the above presented categories. For example, he keeps checking the right takeoff point, watching point by point on a video. Has not yet assessed or cannot yet asses in “whole movement models”. He remains condemned for a while to deal with elements that seem independent for him (e.g. the takeoff leg, the right arm, etc.) without being able to set all these particularities into a larger whole.

For example: A trainer notes that he does not like the fact that his athlete tends to make a certain movement with one arm in the air. He should be doing something completely different. That may be correct, but for the time being, this assessment may also be completely irrelevant.

As a rule, the further you go into the course of a jump, the more irrelevant is the observation. This applies for amateur and experienced jumpers. How someone crosses the bar is the causal consequence of all the movements that were executed before. Is the athlete jumping 5% under his maximum potential, one should not put his thoughts on how he crosses over the bar, there are more important things to correct and put emphasis on. Whoever is looking for a quick success by just improving the bar crossing will have to accept all the previous mistakes, which will solidify and later haunt the athlete for a long time.

One points out to the trainer that he may be right with his selective observation, but that in the big picture the problem starts somewhere else entirely and – this often happens – that the observed „error“ of his athlete is only a „consequential error“, which at best will no longer be detectable if the preceding has been improved or otherwise will occur at least in a weakened form.

Sometimes the athlete and trainer work on technical deficiencies that can not be corrected as long as the preceding factors in the jump sequence are not improved. Due to the lack of experience about the correlation between movements, can a duo of trainer and athlete be stuck in one place for several months or even years. That is why the exchange with, and between experts is so incredibly important. Sometimes even the best expert’s view happens to be obstructed. An exchange between colleagues can help in this case. I regularly exchange with Herbert about my athletes and, for example, at competitions in Germany, I also use the feedback from other coaches, about my athletes but also about my own jumps.

The experienced coach sees any jumper for the first time, for example at a competition, and after 1 jump, without any assistance of a video recording, can tell him about the following, which will benefit the athlete directly:

-Whether he was too close, on point or too far away when taking off. He can also give a statement about whether the run up needs to be corrected (without checking with the jumper afterwards, only based on the fact that he has seen the athlete jump in real time).

-Whether it is the right pole in the athlete hands (too soft, on point, too hard).

-And this in relation to his grip height.

-The position of the standards (too close, just right, too far away – also regarding to what effects the optimizations of the above three points will bring for the next jump – here you can see how experienced Coaches think around three corners in an automatic manner).

An experienced coach captures all of this by simply looking at a jump. It is his wealth of experience that gives him enough data to an evaluation in real time, without video recording.

But even more than that. The experienced Coach could immediately arrange a list of what the athlete should improve in the next few weeks (in case of a professional) and months or years (in case he is more of a beginner to advanced athlete). The elements presented would go from physical to technical aspects, putting emphasis in the latter. And this of course, sorted and brought up in the most sensible sequence.

The experienced coach will not do the mistake of trying to teach the technique to a foreign athlete in middle of a competition. I have experienced that mistake firsthand and know how bad that can go (back then I was an athlete, willing to learn, but not aware that in competition you actually call up on “routines”, and it is not very useful to try to influence and try to change something big in those moments).

The experienced coach stays silent, so that the athletes existing routines don’t dissolve in middle of competition making him start to think. One would think as an example, about the golf or the tennis player, that starts to consider his arm movement before a decisive ball.

Unfortunately, the athletes themselves often commit the foolishness of thinking too much. Understandable, since they mostly still hike the path of knowledge and want to improve. But even I cannot concentrate on more than 1 to a maximum of 2 points when jumping, with 20 years of routine. So, a note to all trainers and athletes that are willing to learn, should be clearly stated here: Never let a “foreign” trainer communicate directly with your own athlete at a competition. The chance that the athlete understands the language of the trainer with exactitude, combined with that he can then implement what he has been told profitably and lastly that he suddenly doesn’t do other things wrong because the focus has been shifted away from his relevant connection points to new ones, corresponds to a pure probability calculation of saying 0.2 x 0.2 x 0.2 = 0.008 which gives a chance of success of 0.8%. So, not a very good idea.

The exchange should be made after the competition, or between trainers during the competition. And even then, the ideas discussed should only be passed on to the athlete during competition, if they are compatible with his current level of experience/understanding. Perhaps in a possibly arrogant way, I deny most trainers the ability to judge whether some advice from a third-party trainer during competition would lead to a slightly positive or a slightly to massively negative result. In a nutshell, it should not be done.

During competition, humans act through learned routines. Everything that disturbs this, leads to a slowing down of the thought processes, and to an awareness of one’s own actions, which is not beneficial at all during competition. E.g., the sprinter who thinks around during the staring steps will with a 100% chance be slower if he keeps consciously thinking these steps, even if he manages to perform these steps better technically.

Well now, how does one reach expertise, as an athlete and as a coach?

It has already been said that it takes time, time of intensive engagement with one’s activity, i.e. in our case long intensive engagement with pole vaulting.

Studies of the already introduced K. Anders Ericcson with the junior squad of the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra have shown that with aspiring violinists it is not the total learning time that decides who will succeed on stage in the end and who will be a still very good violinist but just not good enough to perform on the stages of the world. It is the so-called deep learning that is decisive. The really intensive involvement with one’s activity, as a rule alone, i.e. autonomous from the environment, without distraction. This makes sense when playing the violin or the piano. But also when pole vaulting or playing football.

I’ll start with football. After reading all the books on leaning and expertise, I noticed an article about Lukaku, the Belgian top striker. In the national team, he met top striker and former world star Thierry Henry. That was when two had found each other. They exchanged both, so it was reported, even about the 2nd division games of the German Bundesliga. Two absolute top layers, of whom one could assume that they follow games in the highest leagues in Spain, England, Germany and Italy, sink so deeply into their sport that their interest in what they do even extends to the second division. One could only imagine how many hours these two have devoted to football. Footballers don’t just earn a lot of money. The best ones invest the same amount of time into their sport as the best track and field athletes, tennis players, etc. Ronaldo’s workload on football is tantamount to a mania; you may think what you want about his personality.

From my experience I can report the following, and I will pick out only one factor. When I was about 17 years old, I started to record on VHS everything that was broadcast on TV about pole vaulting, and I mean everything. Every meeting and every report – at that time there was no YouTube, and the number of channels was manageable, so I usually didn’t miss anything. Back then one still had to program the VHS recorder, and one had only 4-hour tapes, which had to be forwarded from jump to jump while watching. With the introduction of DVD recorders, the whole thing was made digitized and edited together. When I came to Peter Keller in 2005, I came across his fund of VHS tapes of pole-vaulting competitions from 1980 (at that time still Super 8 camera) to 1999. I also digitized this to DVD. The result was about 110 DVDs each 70-90 minutes long. In 2009 I stopped recording and collecting since now YouTube had replaced me doing this job. A one-time study of these DVD’s alone results in a time span of 8’800 hours. Among them are also training DVDs of Petrov, Houvion, Alan Launder etc. and portraits of Bubka, Lobinger etc., which I have watched countless times.

This means that nowadays I don’t longer have to think much when I see someone jumping. I usually know what there is to do and can give advice efficiently. This is the case with all experienced coaches and experienced athletes who give advice to their colleagues. The first-person nature of this account is only due to the fact that I only have one experience to share, that being my personal experience.

At this point many coaches, even after X years of activity, are overwhelmed. The long-time coaches, despite the long duration of their activity, because they have not dealt in sum and in intensity with pole vaulting intensively enough. When a surgeon states that during a heart operation he becomes one with his instruments and even feels the patient’s body, then this is translated to pole vaulting as when the coach feels the athlete during observation. He feels what the athlete felt during the jump and can explain this to him in such a way that the athlete receives the advice that meets his understanding and can thus be effective.

How does intense learning (deep learning) involve pole vault? As an example, you play through the effects of different combinations of grip height and pole hardness over a hundred times. You watch an international meeting and set apart who is jumping with which technical variation. If a jump fails, you rewind and find out where the mistake is and so on.

The head “thinks pole vault”

An athlete has a technical problem. Now he starts to think, how do I solve this? What preliminary exercises, what inputs does the athlete need? I think about what the athlete needs to correctly feel in that position. Since we are doing a sport in which you have to feel a lot of things correctly when moving at high speed, in the air and on a pole, it is not easy at all to find pre-exercises or just mental exercises that show the athlete what feeling he should look for and find in the air. An example: I have my athletes hang on a high bar in the take-off position and then press them on the shoulder at the certain point while they try to roll up. This in order to simulate (with the pressure on the shoulder) that they will not roll up on a rigid high bar, but that in reality the pole will actually experience a recoil through the planting box. I keep thinking up exercises like that when I’m on my way to somewhere or can’t sleep (or vice versa, I then can’t sleep because of it).

As a Swiss, one can ask Herbert Czingon about how many hours he spent (intensively) on pole vaulting, which will be far beyond 10.000 hours mentioned.

Expertise follows the intensive study of the sport

You sit at home, watch video after video, take notes, find out what went wrong, think about solutions, invent exercises, and finally write a (solution-) program for the athlete. Of course, what has just been described is to be understood individually, on each athlete.

Not every coach can afford to do that, of course. But it is in the difficulty of our beautiful discipline that athletes only learn efficiently if they are supported individually. Doing the same pole vault preliminary exercises on the pole mat with a group is still one thing that works. But each athlete needs to become individual input to improve. The more efficiently the coach grasps what needs to be done, the more efficiently his athletes learn. Instead of 2 years, they may only need 1 year or in extreme cases instead of 2 years only 2 trainings sessions to learn something. This happens more often than one thinks.

Use your time right. If you are involved in pole vaulting, even if it is only 2×2 hours a week, as a coach who otherwise sees his job and children as the center of his life, use your time intensively to deal with the subject in matter.

Asking the expert

Instead of taking the path of self-knowledge, which is a long one but with the advantage of better adherence in one’s own brain, one should exchange regularly with those who are more experienced or who have just as much experience but usually different experiences, which results in a gain through exchange.

I was allowed to learn from Markus Lübbers (5.30m), Raynald Mury (5.45m), Peter Keller (45 years pole vaulting), Earl Bell (3 times Olympic participant), Gerald Baudouin (5.85m, French national coach) and Herbert Czingon (45 years pole vaulting) and was allowed to accompany Nicole Büchler for many years. I learned a lot from watching my competitors and friends Oli Frey or Boris Zengaffinen and many more.

It often amazes me how quickly younger athletes turn away from the action after a competition. When it’s me jumping, that’s when I personally notice it the most of course, but also when there are others in the action over 5 meters. Dear young athletes and coaches, this would be the moment to learn effectively in real time. To observe. What do they do, how do they move, how do they prepare, at what do they fail, do they find a solution, what do they discuss with their coach. I sat next to the coaches in Monaco when I was 14 years old, of course I didn’t understand a word, but I took note of what was happening on and off the track, then I hurried to the exit and we took photos with Jean Galfione (6.00m) and Romain Mesnil (5.95m). There was motivation involved.

The brain only learns with motivation

When I was outclassed by Oli Frey (which happened quite often), I wasn’t already gone when he was still jumping, I was there, filming, going home, studying him. I don’t have more videos of Oli than he does… but maybe I do. Not everybody has to do the same with everybody. I did it because I knew I brought more kinetic energy from the run-up than Oli, but he had more potential energy at the end, so height. That had to give me a headache, if not, something would have been wrong. And I think here is the point why so few athletes in Switzerland regularly jump over 5.00m (and the same for women at about 4.10m). Coaches as well as athletes do not deal with pole vaulting intensively enough, there is not a lack of talent, there is a lack of expertise on the part of the athletes and coaches. Above 5 meters and above 4 meters, reasonable physical factors are required on the one hand, but above all an intensive examination of one’s own sport. The gap from 4.50m to 5.00m is closed by a jumper who has the potential for 5.70m through his mere physical conditions. He does not close the gap from 5.30 to 5.70m by becoming a little faster in the sprint or a little stronger, it is not sufficient. The decisive factor for this step is that he gradually becomes technically one with the pole, perfects his technique individually and converts his kinetic energy from the run-up into height with maximum efficiency. Mondo Duplantis does this at the age of 18 because he has done nothing else since the age of 4. Without their feeling for the pole vault, Mondo and Renaud would probably just jump somewhere around 5.60m.

So, how do you get the expertise?

Motivation + time.

It is modestly tolerable to go to Magglingen twice a year to attend a lecture by Herbert Czingon and (here comes the decisive link, because it is by no means Herbert’s fault, his lectures are great) to think that this alone brings something. French lessons in high school, of which there were not only 2 per year, but at least 2 per week, were of no use to me for a long time. There was a lack of everything, a lack of motivation, of time and to start speaking of deep learning would be a gross misrepresentation of reality. Admittedly, I was not as fond of my French teacher as I was of pole vaulting, but it is essentially the time, in addition to the lessons, that is decisive for learning French as for pole vaulting. Let us remember the violinists. The time they spend practicing intensively on their own is crucial, not the time they spent in lessons with the teacher.

If a coach or athlete comes to me and asks to borrow 10 of my most important DVD’s to study them back and forth, then…. something can come of it. But only if he gives them back to me after a very/too long time, because he switches back and forth again and again over weeks and months, between training and DVD’s, then observes, what effect does this exercise that I just copied have, then back to the DVD, then analyzes, is there something more suitable for my athletes, back again to the next training, etc. Then, a good coach is born.

This trainer will be able to follow Herbert’s presentation with a much sharper eye and ear because of his already enriched knowledge database. He can create links, his brain „listens“ efficiently, and can ask the lecturer specific questions. The gain from the lecture is incomparably higher. This is what is called the bottleneck of learning. One has to get through the phase in which all loose threads of fragmentary knowledge seem to float in space until these threads form a net, literally a net of communicating brain cells.

Motivation + time leads to a brain that thinks pole vault.

There is no shortcut. Sometimes you find an athlete who is so talented and has good genes that he jumps 5.50m even with poor technique and/or modest support. However, this should not be measured by the absolute height, but by the potential.

This, by the way, is what can make the job of pole vault coach so satisfying, whether you have the next Mondo Duplantis in your training group or just athletes who have the goal of jumping 5 meters or 4 meters one day: You can judge the coach’s abilities by how close he brings his athletes to their possible potential.

This, by the way, is what can make the job of a pole vault coach so satisfying, whether you have the next Mondo Duplantis in your training group or just athletes who have the goal of jumping 5 meters or 4 meters one day: You can judge the coach’s abilities by how close he brings his athletes to their possible potential.

The coach is judged on basis of whether the performance of his athletes is sound, whether the height that an athlete jumps is the result of his good physical condition or of the technical execution.

Georges Martin states about himself that he always had an eye for pole vault. He himself only jumped 4.40m, but that was no barrier. In his over 40 years long career, he coached athletes such as Thierry Vigneron, world record holder (for 3 minutes) at 5.91m and multiple times Olympian, Pierre Quinon, Olympic champion in 1984, Romain Mesnil (5.95m) and Damiel Dossevi (5.75m). The „eye“ for pole vault is a fitting symbolism, an explanation on the metaphysical level. The scientific explanation on a neurological level comes linguistically a bit drier. As a coach, he did not fall from the sky, as the symbolism of the „eye“ seems to suggest. Georges must have had a great interest in pole vaulting from an early age, otherwise he would not have remained faithful to the sport for over 40 years. His motivation was always there, followed by a period of study of the discipline, which he must have started with his training mates and then continued as a coach. It is in this constellation that the cognitive skills of coaching develop (perceptual skills, comparison with the acquired wealth of experience, ability to generate solution options).

No master falls from the sky, there is only sometimes a difference in how one perceives the time of learning. If you want to learn the sport of pole vaulting as an adult with the objective to coach it, the perception of time is different than if you grow up with it as a teenager and as a child acquired the ability to observe, study and thereby learn.

Patrick Schütz – 2021