or why „well-intentioned“ is not good

I took the following mindgame from a book. Unfortunately, I can’t remember the title.

The principle works like this: In a room full of people – an aperitif, a Christmas party – one person raises the question of whether anyone has „seen the black cat.“ The person asking the question knows that there is no black cat in the room, and based on the premises, it is also reasonably easy to determine that there is no black cat in the room. However, by the mere mention of it, it is immediately in the minds of those present and again and again it can be observed how someone is looking for a cat.

The superstition is that a black cat brings bad luck. Although man actually knows from his mind that there is no cat in the room, he still wants to reassure himself again and again that no mischief is imminent.

Where nothing is – is nothing – except in our heads.

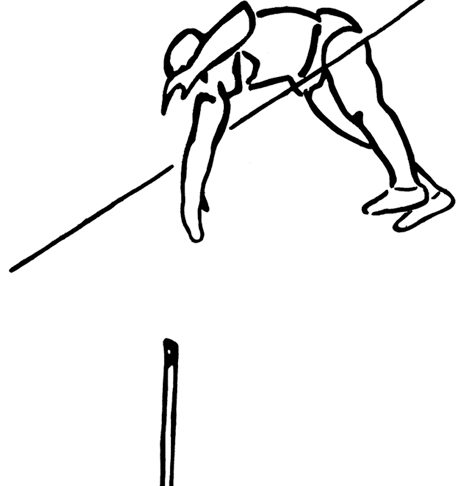

The main application of the principle of the „black cat“ in sports is to mention performance-inhibiting factors („don’t hurt yourself“, „don’t look behind to see if your opponents are coming“). The only effect of this is to make the athlete think about it and stop focusing 100% on what is important, simply performing (just do your job).

For example, the „well-intentioned“ phrase: „I’m glad you’re doing well, I hope you stay injury-free.“ ….

Thank you, says the psychologist (and the coach), now the athlete thinks he is vulnerable. Even if he was in such good spirits before the season started, now the sheer possibility of injury has come to mind. I’m not suggesting anyone got injured because of it. But will the athlete now change anything in the last training sessions before the season? Will he take it easy? Will he go about it with conviction, or will he hear a small voice somewhere in his head telling him, „Watch out, just don’t hurt yourself now.“ The one who said that to the athlete did him no service. „Well-meaning“ is not always good.

Other examples:

„Don’t change anything in your run-up now.“

„Don’t make the mistake again now….“

„See that when you jump you don’t…..“

„Don’t get nervous now…..“

The black cat is the something that isn’t and that you don’t start thinking about until someone mentions it. As a result, it distracts the athlete from what is important.

Another example: When you shout to the athlete, „If you jump over it now on your first try, you’re guaranteed a medal!“

As if the athlete is effectively stupid enough to try less hard on the first attempt without this note…

But now that he’s heard about that medal, his focus is no longer 100% on the movement. Something is now studying around the fact that it is imperative to make a valid attempt. But the valid attempt would be guaranteed by the focus on the movement process – not inversely. The desire for a medal alone does not improve the movement.

Why is that so? Looking at the evolution of mankind, it was quite helpful to remain aware of dangers and risks („Don’t get eaten“). The warning voice had its purpose and still has it today in most areas of application, just less so when it comes to calling up top athletic performance. The goal of evolution was to keep us alive until we had reproduced, and to do this we had to guard against danger. In sports, this protective function is largely a hindrance.

Whoever wants to take into account the principle of the black cat, does not mention anything negative, but formulates exclusively positive and does not mention anything that could distract (like the medal above).

If, for example, an athlete regularly lets his swing leg hang at the decisive moment because he then becomes nervous, then the correct instruction is the one that stabilizes the movement process. This can be the positive instruction to raise the swing leg, but it can also be another input that the athlete and coach know will automatically lead to the swing leg movement being executed correctly (these are the really good inputs). This can defuse and, in the best case, completely eliminate a sticking point in the movement that would be further negatively solidified by the input „just don’t let the swing leg hang now.“

The coach may sometimes find it hard to stand when anticipating a mistake by his athlete. There one must bite oneself as a coach really strongly on the lips, in order not to say sentences like, evenly:

„now, just don’t….“

„now, just not…..“

Conversely, however, one must not forget two things. The athlete is not doing things wrong on purpose. If the athlete is conditioned to „not do things wrong“ at the crucial moment, it fuels fears of failure. If he fails to do it, he has failed.

But when it comes to doing things „right,“ the focus is completely different. If it doesn’t work out, the athlete can say to himself after the competition: Okay, I tried, but I didn’t make it this time.

That’s a key difference that anchors either a positive or a negative mindset.

The second point: learning works through failure. Athletes need to make mistakes in order to learn. The career without failure, it can’t even be invented, it’s basically ruled out.